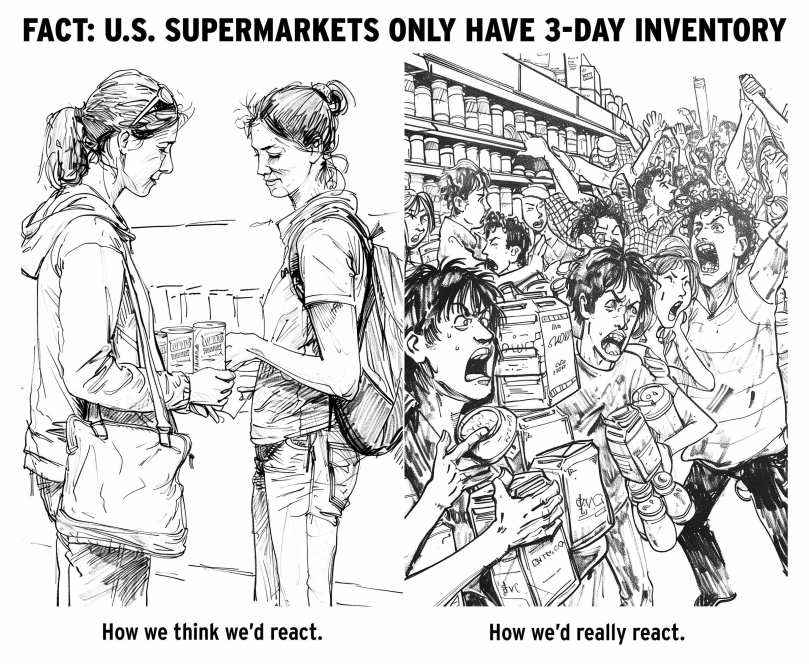

The U.S. food supply chain, often perceived as robust and unshakeable, is far more fragile than many realize. Supermarkets typically hold only a three-day inventory of food. This revelation has raised concerns about what might happen if the food supply were to be disrupted.

The “just-in-time” nature of the food supply chain means that stores receive frequent shipments to keep shelves stocked, minimizing storage costs and reducing waste. However, this efficiency comes with significant risks. If any link in the chain — ranging from farms to processing plants to transportation networks — experiences a disruption, the impact can be felt almost immediately in grocery stores.

A disruption could stem from various sources. Natural disasters like hurricanes or earthquakes can devastate local supplies and cripple transportation routes. Even more insidious are the potential impacts of a major cyberattack or a pandemic resurgence. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, labor shortages at every level — from farm workers to truck drivers — led to noticeable gaps on supermarket shelves and soaring prices.

Jamie Lutz from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) points out that the pandemic caused a significant strain on the supply chain. Increased demand from consumers, who turned to home cooking during lockdowns, combined with labor shortages due to illness, exacerbated the situation. The result was a sharp rise in food prices, making it harder for families to afford basic necessities.

Toby Hemenway, an expert on food security, explains that while the food system is indeed complex and adaptive, it’s also highly interdependent. This interdependence means that a disruption in one area can cascade through the system, causing broader impacts. He suggests that localizing food production and diversifying supply chains could help mitigate some of these risks. Hemenway argues that storing vast amounts of food in urban areas is less effective than ensuring a steady flow of goods through a resilient and flexible supply chain.

If a severe disruption were to occur, supermarkets could run out of food in just a few days. This would lead to panic buying and hoarding, further exacerbating shortages. Vulnerable populations, such as those relying on Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, would be particularly hard hit. The federal government attempted to address these vulnerabilities by temporarily increasing SNAP benefits during the pandemic, but these measures are short-term solutions to a long-term problem.

While the U.S. food supply chain is designed for efficiency, its lack of redundancy makes it vulnerable to disruptions. Preparing for these potential crises involves not only improving the resilience of the supply chain but also encouraging local food production and ensuring that all communities have access to emergency supplies. The complexity of the system requires comprehensive strategies to protect against the myriad threats that could lead to empty shelves and widespread hunger.

DO YOU WANT TO KNOW MORE?

The state of grocery in North America