Switching to Merriam-Webster is probably a good idea. However, didn’t anybody see a problem with the annoying words here? Sheesh.

Switching to Merriam-Webster is probably a good idea. However, didn’t anybody see a problem with the annoying words here? Sheesh.

As a longtime New York Times subscriber, I appreciate the depth and breadth of its content, particularly the extensive online archives dating from 1851, and its coverage of arts, entertainment, and international news.

Yet, I’ve grappled with the paper’s editorial stance, particularly its approach to domestic news, which I perceive as being distinctly elitist and favoring a progressive, globalist viewpoint.

The Times’ appointment of Zach Seward as Editorial Director of A.I. Initiatives marks a significant step toward integrating generative AI into journalism.

Seward, with his impressive background as a founding editor of Quartz and a stint at The Wall Street Journal, is set to lead a small team focusing on the application of AI in news reporting. His role includes establishing principles for using generative AI in the newsroom and ensuring that The Times’ journalism continues to be reported, written, and edited by human journalists while AI tools assist them in their work.

This development brings to the forefront an intriguing proposition: Could AI play a role in addressing biases in reporting?

For instance, employing AI in copy editing might introduce a level of objectivity that I feel is sometimes missing in The Times’ reporting.

If configured to uphold impartiality, an AI-driven copy desk could potentially mitigate the paper’s perceived bias toward progressive viewpoints and its narrative on climate change and social disparities. This approach might balance the editorial tone, addressing concerns like mine about the paper’s leaning.

In conclusion, while The Times remains a valuable source for its archival content and global reporting, its foray into AI under Seward’s leadership presents an opportunity to explore new frontiers in journalism.

Perhaps, with careful implementation, AI can bring a fresh perspective to the newsroom, potentially addressing longstanding concerns about bias in media reporting.

Once upon a time, The New York Times was my morning oracle. A cup of coffee, the crisp pages of the Times, and I was informed, enlightened, and ready to face the world with a mind full of facts.

Ah, those were the days!

But alas, that Times, the beacon of journalistic integrity, seems to be nothing more than a quaint memory, replaced by a publication that to me is less about news and more about … well, let’s say selective storytelling.

Case in point: the recent unsealing of the Jeffrey Epstein files. Now, one would think that the revelation of a high-profile scandal involving a notorious figure would be front and center, right? But no. In its infinite wisdom this morning, the Times decided this was little more than a “More News” item. Less important than an audio feature in which Oprah Winfrey and Gayle King “discuss their friendship” and an article about flowers having reduced sex (I kid you not).

I couldn’t help but chuckle (bitterly, mind you) at the irony. Here we have a story with everything – intrigue, high society, scandal, sex – and The New York Times treats it like a bus plunge. What happened to the fearless pursuit of truth? To the paper that once brought us groundbreaking stories with unflinching honesty?

It’s clear that The Times has become a water carrier for the left, carefully curating news to fit a certain narrative. Gone are the days when it stood as a paragon of unbiased reporting. Now, it’s more about what they choose not to report, and how quietly they can do it.

I’d wipe my ass with The New York Times, but the ink might undo the anal bleaching.

Oroville (California) Mercury Register

October 2, 1943

(Scan of newspaper page bottom incomplete.)

It was a big day for I-DEP, a Chicago-based dot-com startup poised to ignite a new era in conducting remote legal depositions.

I-DEP’s tech team had found a way to seamlessly merge video, audio, real-time court reporter transcript, and secure private chat into a single, easy-to-use service.

This stuff is routine now, but in 2001, amalgamating the technologies to accomplish all this was bleeding-edge.

To show prospective clients how the I-DEP system worked, we’d improvise a brief sample deposition where staffers portrayed attorneys, plaintiffs, and defendants. At the same time, actual court reporters entered the live transcription.

On that day, we were on deck to hit a home run.

I-DEP had been invited to strut our stuff at a meeting in Washington, D.C., before a meeting of state attorneys general and federal prosecutors. I’d penned a script for a mock deposition inspired by Michael Fortier’s testimony in the McVeigh trial. Darkly ironic, it dealt with domestic terrorism. Showtime was close, adrenaline fired up.

I-DEP was ready for our closeup on September 11, 2001.

Then, the world shifted. Twin Towers, Pentagon, United Flight 93. All crashed and burned. A different kind of terror script, one you couldn’t delete or rewrite. Our team en route to D.C.? Uncertainty gripped us. Hours later, we determined they were OK. But we couldn’t say the same for nearly 3,000 others.

In the following days, the media got under my skin. They were already wringing politically correct hands over how to assess this attack. Or claiming that Todd Beamer “reportedly” or “allegedly” declared “Let’s roll!” as doomed passengers heroically prevented Flight 93 from being used as a weapon.

I also forced myself to look at those photos. The ones showing desperate souls leaping from the Twin Towers. Each image was an indictment, a promise from history that we’d forget too soon. Somewhere in those snapshots, the world’s tough questions lurked.

In the years that followed, everyone talked about resilience and heroism. All justified, sure, but what about the questions, the actual interrogation? People compared 9/11 to Pearl Harbor. Remember the Alamo, never forget; catchy slogans that fade into bumper stickers. Meanwhile, the tough questions remain AWOL.

I did my job and hit my PR targets in the aftermath.

But September 11 changed the script and not just the one I wrote. Some things can’t be revised or redacted. Questions remain forever unanswered.

There are no clean edits in real life. And that, as they say, is the hell of it.

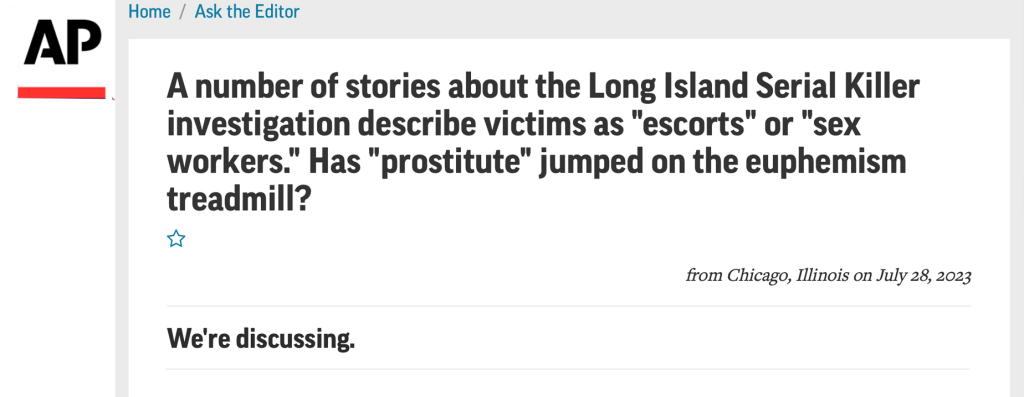

I queried AP Stylebook’s editor a few days ago about whether it’s preferred to discontinue “prostitute” in favor of “sex worker” or “escort.” Below is a screenshot of the response I received today. How do you think the AP should decide?

See my original post on this issue.

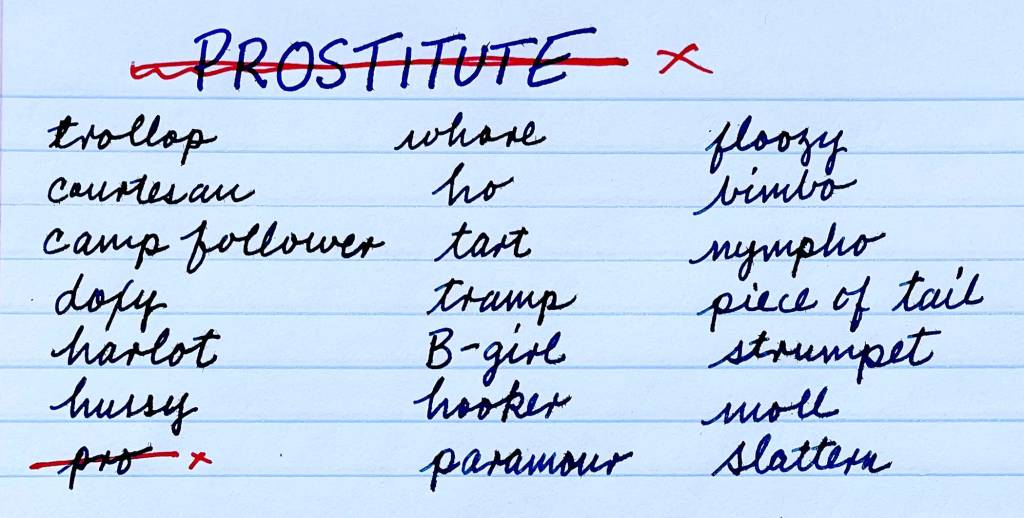

I’ve been noticing something strange in the news lately. Many news stories about the Long Island Serial Killer no longer refer to some victims as prostitutes.

The media’s preferred term is becoming “escort” or “sex worker.”

But why is that? And why should journalists still write “prostitute”?

Forget about being politically correct. Yes, we should usually respect how people want to be identified and avoid using hurtful words.

But let’s be honest: Most prostitutes do it because they are desperate or forced. Saying “escort” or “sex worker” makes it sound like a regular job, which it sure as hell wasn’t for them.

Using the word “prostitute” reminds us of the harsh truth about sex work. It’s a trade in which people are taken advantage of, often in terrible ways. It tells us we must help those caught in this situation.

If we use nicer-sounding words, we forget how serious and urgent this problem is.

So, who wins when we change the words we use?

People who want us to see sex work as just another job like these new words. If we think of sex work as normal and not something terrible, it might help their cause. But that view forgets about all the people forced into prostitution because they’re poor, addicted to drugs, or because someone made them do it.

Also, as a society, we don’t like to face harsh truths. Using nicer words helps us feel better and keep a safe distance from real problems.

But here’s the thing: A journalist’s job is to tell the truth, not make people feel good.

Remember that we shouldn’t use the word “prostitute” in a mean way. The Long Island Serial Killer’s victims were real people with families and friends. Their lives mattered, and they died horribly.

Journalists must recognize the hard truths to tell their stories right and not hide behind more sociable words.

Journalists should keep writing and saying “prostitute” because it shows how bad things are for some people and reminds us we need to help.

In today’s world, many news stories are influenced by personal views or politics. This is a big problem for the news business. Now, Google has made Genesis, an AI bot that writes news. This might be a big step toward information that is fairer.

When we talk about “fair” news, we mean information not influenced by views or politics. Readers should be able to make their thoughts based on the facts. Recently, communication has become more influenced by personal or political beliefs.

AI, like Genesis, has no political or personal views. It doesn’t have feelings that can cause it to be biased like humans. AI uses algorithms to find, sort, and show data. It doesn’t form views.

Genesis can mine many data sources and find, sort, and show it faster and on a larger scale than humans. It can check these sources for facts and make complete, balanced reports without views or slants. This not only means more topics can be covered but also that the points stay true.

However, can pick up biases from the data it uses to learn. For example, if an AI uses a lot of data from one political view, it might show that view in its work. So, the people who make and use AI have a big job to ensure the data is fair and the AI is used correctly.

Also, AI can’t replace human news writers. Genesis is good at finding and showing facts, but humans understand feelings and complex ideas better. The best way forward might be for AI and humans to work together: Genesis can give the points, and humans can provide the meaning and tell the story.

Genesis is a big chance for the news business. News that is just facts could make people trust information again. However, it is essential to remember that AI is a tool, not a magic fix. Making sure news is fair requires hard work and care from those who create and use AI. If we use Genesis correctly, it could start a new time of unbiased news.

If we use AI like Genesis thoughtfully, we could move the news business away from views and back to truth and fairness. In a time where false news and over-dramatic stories have made things unclear, AI could be the guide to help us understand the world fairly and clearly.